Geological Formation Properties and Their Impact on Drilling

- Published August 2, 2025

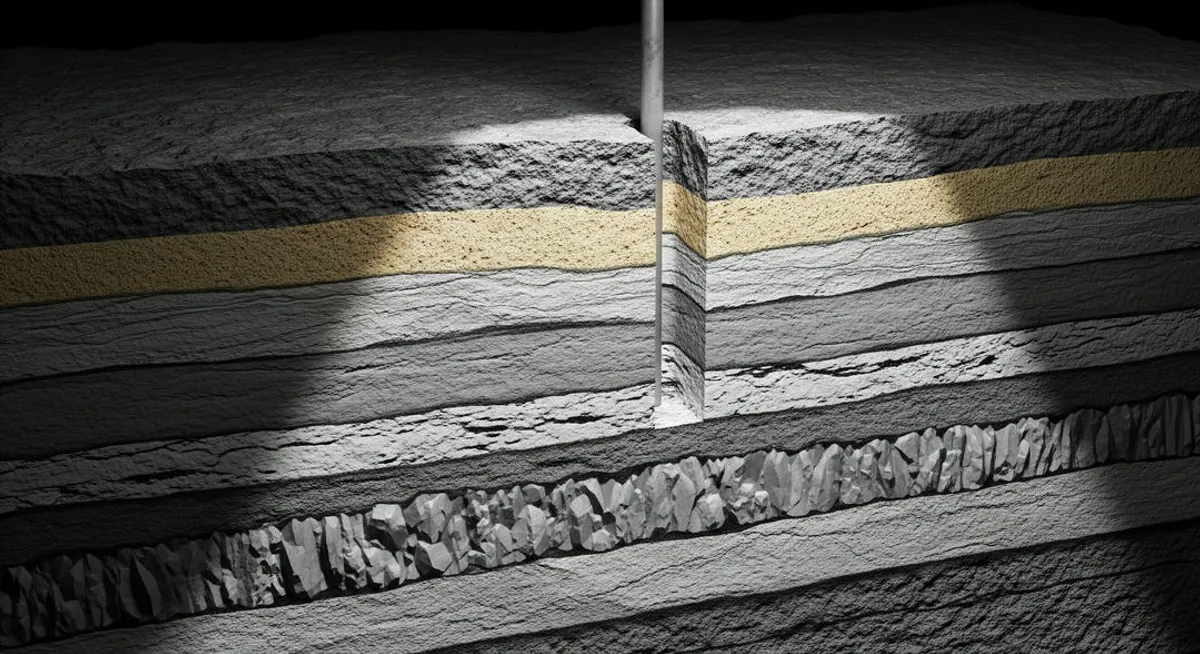

Oil drilling is a constant dialogue between engineering and geology. The properties of the geological formations a well encounters determine the strategies, tools, and fluids needed to drill efficiently and safely. This chapter focuses on the key characteristics of formations—hardness, abrasiveness, and stability—and their impact on drilling, with examples such as shales and sandstones. Additionally, it explores how surface and subsurface geological maps guide well planning. By understanding these concepts, you can connect petroleum geology fundamentals with well types and equipment covered in later chapters.

Geological Formation Properties

Each geological formation a well penetrates has unique physical properties that affect drilling. These properties, determined by mineral composition, texture, and subsurface conditions, influence bit selection, drilling fluid design, and strategies to maintain well integrity. The most critical properties are hardness, abrasiveness, and stability.

Hardness

Hardness measures a formation’s resistance to bit cutting, determined by its mineral composition and rock compaction. For example, sandstones are typically less hard, facilitating drilling, while compact carbonates, such as limestones, or igneous rocks, like basalt, are extremely hard, reducing the rate of penetration (ROP). Hardness is assessed using scales like Mohs or laboratory tests on rock cores.

In a well in the Permian Basin, a soft sandstone formation allows the use of standard tricone bits, while a hard limestone may require tungsten carbide insert (TCI) bits to withstand the stress. Hardness also affects bit wear, requiring adjustments to weight on bit (WOB) and revolutions per minute (RPM).

Abrasiveness

Abrasiveness measures the extent to which a formation wears down the drill bit due to the presence of hard minerals, such as quartz. Sandstones with high quartz content, common in sedimentary basins, are highly abrasive, reducing bit life. In contrast, shales tend to be less abrasive but can complicate drilling due to their plastic behavior.

For example, in the Vaca Muerta formation in Argentina, quartz-rich layers require polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) bits, designed to resist wear. Abrasiveness influences bit selection and operational costs, as excessive wear may require multiple bit changes, increasing non-productive time.

Stability

Formation stability determines its ability to maintain well integrity during drilling. Unstable formations, such as reactive shales, can swell upon contact with water, causing collapses or stuck pipe. Shales rich in clays like montmorillonite are particularly problematic, as they absorb water from the drilling fluid, leading to wellbore collapse or narrowing.

In contrast, well-cemented sandstones are typically more stable but may fracture under high pressures, causing lost circulation. To stabilize unstable formations, engineers use specific drilling fluids, such as oil-based muds or clay inhibitors. For example, in a well in the Gulf of Mexico, an oil-based mud can prevent shale swelling, while a water-based mud might cause issues.

The following table summarizes the properties and their impact on drilling:

| Property | Example Formation | Impact on Drilling | Technical Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness | Compact limestone | Reduces ROP, greater bit stress | TCI bits or WOB/RPM adjustments |

| Abrasiveness | Quartz-rich sandstone | Rapid bit wear | PDC or reinforced bits |

| Stability | Reactive shale | Risk of collapse or stuck pipe | Oil-based muds or inhibitors |

Use of Geological Maps

Geological maps are essential tools for drilling planning, providing a visual representation of subsurface structures and properties. These maps are divided into two main categories: surface and subsurface, each serving a specific purpose in well planning.

Surface Maps

Surface maps show visible surface geology, such as rock outcrops, faults, or folds. These maps help identify potential geological traps, such as anticlines, which may indicate the presence of hydrocarbons in the subsurface. For example, a surface map in the Neuquén Basin, Argentina, might reveal an anticline suggesting a trap at depth.

These maps are created through field observations and satellite data and are useful in the initial exploration phase. However, their utility is limited, as surface geology does not always reflect subsurface conditions, especially in regions with complex sedimentation.

Subsurface Maps

Subsurface maps, generated from seismic data, well logs, and geophysical studies, represent geological structures at depth. These maps are critical for planning well trajectories, especially in directional or horizontal drilling. For example, a subsurface map might show an anticlinal trap at 3,000 meters, with a sandstone reservoir sealed by shale.

Seismic data, obtained by sending acoustic waves into the subsurface and analyzing their reflections, allow mapping of interfaces between formations, such as the boundary between a shale cap and a sandstone reservoir. Well logs, such as gamma ray or resistivity, complement this data, providing insights into formation properties. In a well in the North Sea, a subsurface map might guide drilling to keep the bit within a productive sandstone layer.

Integrating surface and subsurface maps enables engineers to anticipate changes in formation properties and plan well design, from bit selection to casing setting depth. This information is crucial for avoiding issues like lost circulation or collapses, directly connecting to stability and drilling concepts covered in later chapters.

Summary

The properties of geological formations—hardness, abrasiveness, and stability—determine technical decisions in drilling, from bit selection to drilling fluid design. Reactive shales and abrasive sandstones present unique challenges requiring specific solutions, such as oil-based muds or PDC bits. Geological maps, both surface and subsurface, transform geological data into practical tools for precise well planning. These concepts connect petroleum geology with well design and drilling equipment.

Practical Exercise

- Reflection question: How do you think formation stability affects the safety of a drilling operation, and why is it important to anticipate it?

- Research task: Investigate a known reservoir (e.g., Eagle Ford in the U.S.) and write a paragraph describing how its formation properties, such as hardness or stability, influence drilling strategies.

- Technical question: Explain how a subsurface map helps prevent issues like lost circulation during drilling.

Bibliography

-

Books used:

- Hyne, N.J. (2012). Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling & Production. PennWell Books.

Explains formation properties and their impact on drilling. - Selley, R.C., & Sonnenberg, S.A. (2014). Elements of Petroleum Geology. Academic Press.

Details the use of geological maps and formation characteristics.

- Hyne, N.J. (2012). Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling & Production. PennWell Books.

-

Recommended books:

- Bjorlykke, K. (2015). Petroleum Geoscience: From Sedimentary Environments to Rock Physics. Springer.

A technical resource on formation properties. Available at: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783642341311. - Bourgoyne, A.T., Millheim, K.K., Chenevert, M.E., & Young, F.S. (1986). Applied Drilling Engineering. SPE Textbook Series.

Analyzes how geological properties affect drilling. Available at: https://store.spe.org/Applied-Drilling-Engineering-P11.aspx.

- Bjorlykke, K. (2015). Petroleum Geoscience: From Sedimentary Environments to Rock Physics. Springer.

-

Direct links:

- SPE (Society of Petroleum Engineers): Resources on geology and drilling. https://www.spe.org/en/.

- AAPG (American Association of Petroleum Geologists): Information on geological maps. https://www.aapg.org/.

- PetroSkills: Courses on geology applied to drilling. https://www.petroskills.com/en/training/courses/petroleum-geology-for-non-geologists---ng.